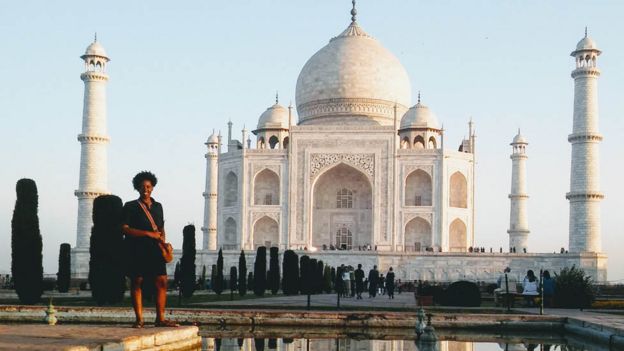

Ashley Butterfield, 31, has been around the world - but a visit to India brought home the particular challenges of being a lone black female tourist.

"Are blacks better in bed because of genetics or diet?" the middle-aged Indian restaurant owner asked me earnestly as I finished the dinner he had prepared.

Although not a question that one typically expects when requesting the bill, I was not unsettled. Having worked in international development for the past seven years and having travelled in 30 countries, mostly alone, I have grown accustomed to hearing things that most people would find jarring. However, I didn't feel defiant, upset or even threatened by him.

This was not the first time I'd experienced this sort of thing.

Once I fell asleep on a bus in north India and woke up to a man, inches away from me, videoing me on his phone.

"What are you doing?" I asked, alarmed.

He simply replied: "Instagram."

In Udaipur, a man approached me in a restaurant and kept telling me how much he loved black people. Then he started making comments that were sexual.

The attention I received was not always extreme, but sometimes the energy changed when I was with other travellers. There was a clear difference in the type of attention that I received when walking with fellow white or Asian travellers, versus when walking alone or with another black person.

When with the former, people still noticed me, but their reactions were more indifferent than negative, as if the other travellers validated my being there. When alone or with another black person, however, a large majority of the reactions toward us were decidedly negative - expressed through frowning faces, laughter, pointing, staring, making jokes or hurrying away from us.

After university, like a lot of young people, I wanted to see the world and do something meaningful that would show me different societies and cultures. Following a gruelling screening process, I was selected for a two-year position in Africa with the Peace Corps - a competitive international volunteer programme run by the US government.

Having come from a family in Florida who only wanted to vacation in places that were accessible by car, I had never flown on a plane, let alone been out of the country. At 22, I found myself boarding my first international flight to the then Kingdom of Swaziland (recently renamed eSwatini by its monarch), a small country that borders South Africa and Mozambique.

The adventure was uncharted territory for me and it was thrilling.

Shortly after arriving in Swaziland, I started to realise how skewed my opinion of Africa had been, which both shocked and saddened me. Prior to Swaziland, my impressions of Africa, and indeed Africans, had been shaped by movies, National Geographic magazines and the Discovery Channel. At that time, the people displayed through those media outlets were often depicted wearing bright tribal clothes that left them partially nude, they hunted animals with spears and waged tribal wars often, and they sat on dusty floors in mud huts while cooking things in clay pots. Their lives seemed so exotic, so other worldly.

However, in Swaziland, I found the people and their activities to be quite familiar- so much so that I often grew bored. Yes, there are cultural differences, including cultural events that are unique to the region, but the day to day life of a Swazi closely mirrors that of those in the Western world.

Swazis are normal people with normal worries - people who think about school, getting to work on time, music, relationships and popular culture like everyone else.

The country, just like the US, is diverse. There are city people and rural people, the affluent and the less fortunate, the good, the bad, the lazy, and the hard-working. More importantly, through it all everyone manages to stay fully clothed and the spears stay tucked away. I wondered why this side of Africa was never shown.

But the biggest surprise was how I was treated. It wasn't a warm embrace.

AFP

AFP

The Peace Corps had selected the community I would be staying with and the people there had been told to expect a US volunteer.

"When is the American getting here?" I was asked on arrival.

I am the American, I said. They were shocked. Just like I had images of what a typical African should be, they too had an image of a typical American. And that was not a 22-year-old black woman.

To them, I was a fake American. Some even suggested that I was a spy from an English-speaking African country. This is not an uncommon reaction to volunteers of colour. In addition to black volunteers, Asian, Latino, and Native American volunteers are sometimes greeted by disappointed community members who assumed that they would look different - that they would be white.

I completed my two years of service in Swaziland with the Peace Corps. Despite continual challenges that I faced there due to my race, I stayed - because being there meant that I was continuing to learn more about Swazis, as well as allowing Swazis to learn more about me. Following my time there, I travelled from south to north Africa, mostly overland, to further enhance my knowledge about Africa's diverse cultures and people.

I returned to the US and secured a leadership position with the Peace Corps, but five years later I decided a break was in order.

So last summer, after turning 31, I left America for a trip around Asia. I planned to wing most of the trip, but decided to position myself in India for March, to specifically coincide with Holi, the vibrant Hindu festival in spring where people throw coloured powder and water at each other.

I'd been wanting to go to India for years. Back home in the US, I didn't have any close Indian friends who could tell me what to expect, so I relied on books and the internet to prepare for my trip. This would be a whole new experience for me.

Seven weeks ago I landed in New Delhi. The first thing I noticed were a lot of dogs, trash everywhere, a lot of noise, and a lot of people. This was truly a whole new world.

By the second day I started to find the experience unsettling. I noticed as I walked through the streets, people began pointing, laughing and running away from me.

Crowds would rush to clear a path as I walked by. On day two a group of feral dogs, very common in the capital, began to approach me like they were going to attack me. Despite my fear and distress, the people nearby seemed to find this to be hilarious.

The commotion of the dogs, my shouts, and people's laughter had resulted in a crowd forming around me. Once the dogs had retreated, people started throwing water balloons at me. I protested, but it wasn't until I was quite wet that an older gentlemen told the crowd that I'd had enough. On the wet walk back to my hotel, I told myself that the experience was related to Holi, but unlike what I read about Holi, it didn't feel playful - there was an edge to it.

I had been travelling around Asia since August 2017. Like many tourists venturing into communities lacking diversity, I've been used to being stared at, but the attention I received in India felt different.

The looks didn't seem like expressions of curiosity. They seemed sinister and unwelcoming. When people (young and old) see someone with black skin they stare, point, laugh, make jokes, clear paths, run as if you are chasing them, and fix their face to display an overall look of disgust. Too many people were rude, incredibly childish and treated me poorly. When not being ostracised, I was fetishised.

One of the most pivotal experiences came when a middle-aged man asked me, innocently, about the sexual prowess of black people.

I realised that before I went to Africa I was misinformed about Africa. The same was happening the other way round.

I began to think of my experience in Swaziland. How I thought of people as hunters who ate from clay pots and how they thought of me as a spy.

"Where are you getting that information from?" I asked the man calmly.

He said he had seen black women on TV walking around without many clothes on. They were jumping around and seemed to have a lot of stamina, he told me. He specifically cited the Discovery Channel and porn as his sources. I realised that he had been fed a particular image of black women. Having understood just how impactful the teaching of the media can be, I talked to him about ratings, viewership, typecasting and acting.

In addition to my sexual powers as a black woman, my hair also seemed to be other the minds of many. At one point a group of teenagers came up to me and asked about hair, as they thought I was wearing a curly wig.

I was happy to explain it to them, as I understand that people are curious about natural black hair.

For years black women have worn their hair straight or in braids, so the black hair experience is new for many. It's only recently that we have been seeing black women and mainstream media embrace natural hair - and I am happy to welcome and educate others who want to be part of the experience.

That's the thing with my experience. I'm happy to talk about our differences and bridge any barriers. Is it always friendly? Definitely not, but when I feel down, God appears to me in small ways.

Once I was on a very long bus ride for around seven and a half hours from Jaipur to Udaipur in Northern India. A woman who was about 45 sat next to me. She made sure I was taken care of for the whole journey. She made sure I made it back on the bus at stops, that I knew where to find the restroom. She gave me snacks.

For this part of my journey, I felt relieved to have an ally.

This issue is much bigger than just me - than just one black woman sharing her experience.

I'm in a Facebook group of former, current, and would-be black volunteers. We have the group to show support to each other through various experiences that are common and uncommon before, during and after Peace Corps.

We often talk about issues impacting on us while working and travelling abroad and we'll agree that representation is the key where ever we are. Which is why, although it can be extremely unnerving at times, I make it a point to be as visible as possible when I travel. I never shy away from big crowds, although crowds are where I receive an exaggerated version of hostility.

My goal is to allow as many people as possible to see me. I want people to see me so much, until they get bored with seeing people like me. I hope the world that the next generation travels in will be a world where people are bored with seeing black people with natural hair. Lastly, it is my hope that the US moves forward with plans to put Harriet Tubman - a black American and abolitionist - on the $20 bill. Such representation will play a vital role in ensuring that people all over the world see and understand the diversity of America. Given that the US dollar is so widely used internationally, she would be such a powerful ambassador - ensuring that people like me can spend less time explaining and enduring - and more time creating and having positive experiences abroad.

My dream is that in the not-too-distant future people all over the world get so used to seeing black people, especially lone black women travellers, that by the time the Generation Z black women start exploring the world, we won't be so sensational. We can be observers like every other traveller.

So I'll keep on travelling the world to make sure my face is seen.

As told to Megha Mohan @meghamohan

You might also like:

"This is why hair maintenance is so important to the black community. We learn to endure the pain of our mothers and aunts braiding patterns into our scalps. We spend a small fortune on butters, oils, and creams. We sit in the salon for hours on end to achieve the perfect look. And after all that we're judged - no matter what we do."