By Yakubu Mohammed

Nigerian Senate PHOTO:Twitter

On this occasion, at least, I hate to claim that I am being proved right. But that seems to be my reading of the situation since the governors from the southern states threw their political gauntlet recently. At their Lagos meeting on July 5, a follow-up to their unprecedented Asaba summit, the governors issued a communique in which, among other weighty issues, they demanded, as a right, that in 2023, the president of this country must come from the South.

Though unusual in a multiparty democratic setting, in which each political party, using constitutionally provided selection process, has untrammeled freedom to pick its candidates from any part of the country, this demand, I must admit, threw up not a small dot-like ruckus in the political firmament.

And the reaction from some section of the North was predictably harsh as if this demand, usually and reasonably allowed political pressure groups, is tantamount to treason. One group that claimed to have spoken for the political North betrayed its lack of understanding and its absence of a nuanced grasp of the dynamics of politics when it went before the media to claim that the North’s hold on power was unshakeable.

Yes, it may be so but their argument, as presented by a Dr Abdullahi, was to say the least, banal. Definitely not something that would have done the North proud. Their main argument is that politics is a game of number. And he proceeded from this universally acclaimed democratic credo to reel out the statistics that would make the North’s electoral position, based on its numerical strength unassailable. The population of the North, he claimed, was 120 million. And the population of the Fulani is 40 million. Now, hold your breath, this mathematical political guru moved gloriously to the next level by adding the population of Fulani, apparently but inexplicably a separate entity, to that of the North. With flourish, he announced the North’s total voting strength of 160 million. Nobody, to the best of my knowledge, has challenged this arithmetic: where are the 40 million Fulani voters from? Are they, like the Tiv, the Idoma, the Jukuns and the Igala, not part and parcel of the North? Why would anyone add their separate number to the population of the North?

Happily, those men of understanding, who hold the levers of power in the North, including the governors and other political juggernauts did not engage themselves in this inane game of defending the indefensible.

Without any doubt, the South has a right to ask that the next president should come from their region, by election not by selection, but as Governor Babagana Umara Zulum, may Allah bless this foresighted and eminently sensible governor, pointed out, it was wrong for the governors to use the word must in their demand.

Politics is a game best played by those gifted with the art of deal making, consensus building amid back-slapping, not to say anything about back-stabbing. For a few gentlemen like Governor Zulum, it is also a game in which the God-fearing must keep to the rules of engagement and, what is most important, their agreements; their words must be seen to be their bonds. Speaking on Channels Television programme, in reaction to the demands of his colleagues, Governor Zulum says he stands by the position of his party, the All Progressives Congress, APC which has zoned the presidency to the South. That, in my view, speaks volume.

Somehow, I did not believe that this day would come. Or come so fast. In 1991 I wrote a column titled the “wild, wild North” having taken a pictorial look at the unceasing riots in the North blowing like harmattan wind from Kano to Yola, to Maiduguri to Kafanchan to Kastina and to Bauchi. I thought the North which the then Sultan Ibrahim Dasuki had called a bedrock of disturbances had upstaged the West which had dubiously laid claim to that epithet in the wild days of the First Republic politics.

The North, for a very long time since independence, had an exclusive, almost monopolistic hold on political power, apparently its own share of the equitable division of labour in which the South played the exclusively, dominant economic role. But I had predicted in the said column that with the endless feud, the impression was being created that the North could not keep its house in order and soon it would make sense for people to question the morality of continued political dominance by those who could not put their house in other.

Precisely this is what has begun to happen. Those who seemed happily contented with the North’s position hitherto are today beginning to make demands. The heated debate about restructuring and devolution of power is not an endorsement of what the North has done with power or the way it has governed the country. It is a vote of no confidence.

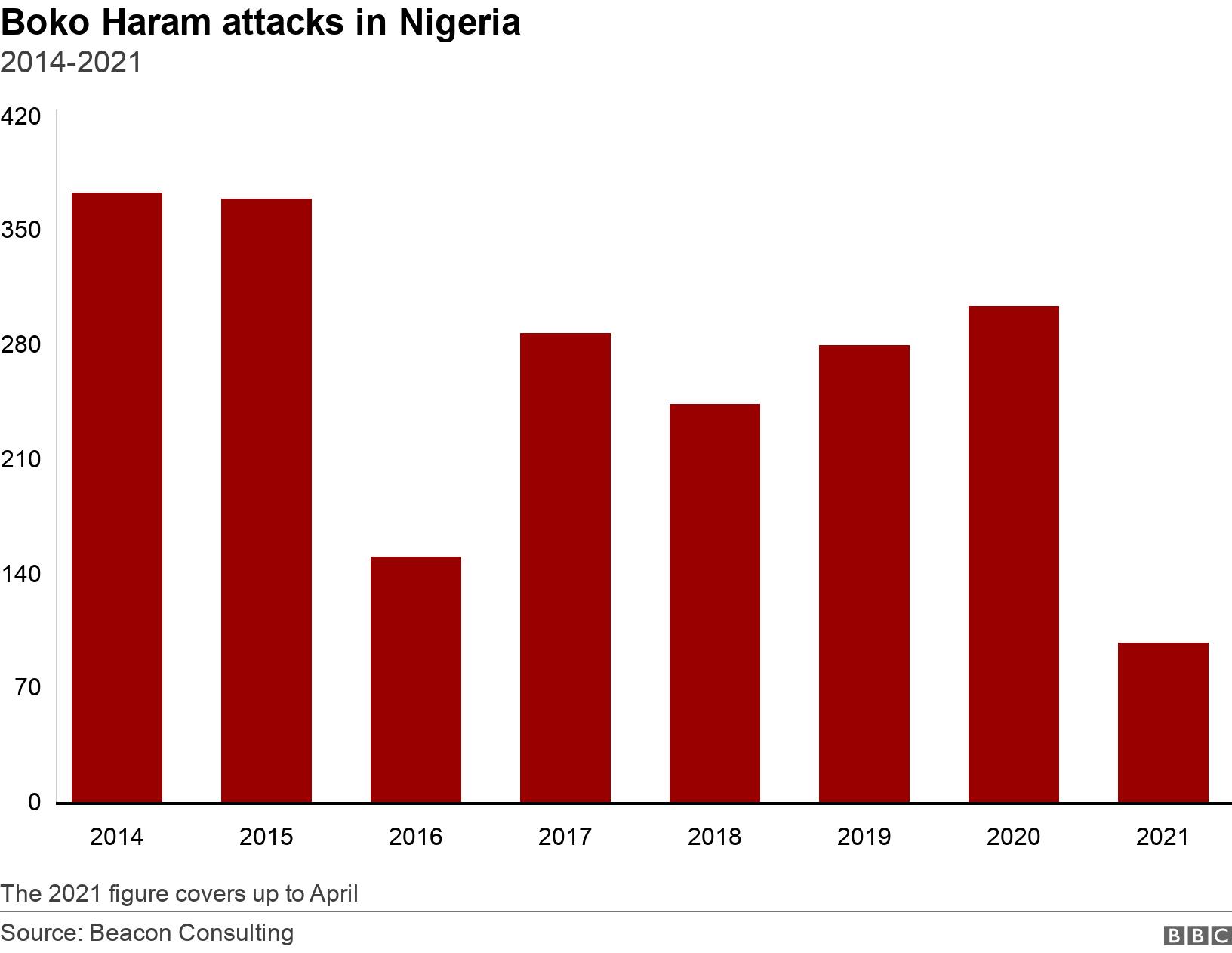

Nobody I dare say is happy with where we are today, though it took a long time getting here. No soothsayer, no pastor or Imam or any of the itinerant babalawos had foretold that a time would come in this country when bandits, kidnappers, Boko Haram insurgents, rapists and other nondescript criminals would take hold of the country and dictate how we should live our lives.

Today this abnormality in our social and economic order has become, like COVID-19, the new normal. One is not sure of anything. Farmers have to pay terrorists to be allowed to go to farm. And they have to pay them protection fees to allow them to harvest. And they cannot freely transport their farm produce to the markets. Social insecurity is now compounded by food insecurity. That is the veritable definition of national famine. And calamity.

And yet there is no let up. As of the time of writing, bandits who kidnapped students of Bethel Baptist High School, Kaduna on July 5, are still holding about 85 of the students, having released 28 of the students on Sunday on collection of N50M ransom. In Niger State, 136 pupils of Islamiya school in Tegina are spending almost 60 days in captivity this week while in Kebbi State, 83 students of Federal Government College, Birinin Yauri are being held hostage to be released only when security men release their leaders who are in lawful custody. Schools have had to be closed down indefinitely to protect students from being harvested for ransom.

I did not bargain for this level of insecurity and absolute lawlessness when I called on our leaders to take proactive steps to nip in the bud violence occasioned by religious intolerance and ethnic bigotry. But as I said at the time “the leaders in the North – traditional, religious, political, military and even intellectual – all of them in their brazen pursuit of mundane perishability, seem to me to have failed woefully to pull the region back from the brink.”

That monumental failure to act when acting would have saved the situation is part of the reasons we are in this monumental tragedy today.

What was unthinkable before is now a reality, a daily routine. Nothing is sacrosanct any more. Not even the place of worship – church or mosque. Traditional leadership is neither sacred nor hallow. Emirs, in their flowing robes and turban, are being plucked down from their thrones and taken captive by the outlaws. And they would not be released until they have been traumatized and until heavy ransom is paid.

Now that we seem to have had enough blame game, is it not time for the North to wake up and do more serious introspection? The region which at the best of time was only lumbering sluggishly behind the South pretending to want to catch up, is now brought to utter comatose status. A giant leap out of our desperate situation, therefore, would require some kind of Marshall Plan and our leaders must begin today to address their minds towards that survival mechanism.